In a little street behind Casablanca’s historical Palace of Justice and the imposing French consulate, a small hidden house turns out to be an institution of traditional Moroccan gastronomy. The luxuriant garden has taken over the wooden entrance door and conceals the suspended sign where you can barely read the name “Al”. Pastel purple petals, fallen on the pavement, form a soft carpet for guests entering a shady patio. There, it is either time for a refreshing lunch break or a romantic candlelight dinner.

Al Mounia opened in 1958, shortly after the Independence. The great-uncle of Mrs. Berrada, the proud and sturdy current proprietor, noticed that Casablanca’s city center was filled with French restaurants, but lacking the authenticity of Moroccan traditions. Hotels failed in their attempt to serve a Moroccan meal, distorting original customs. In Al Mounia’s dark and cosy interior, refined azure zelliges (terra-cota tileworks) stand alongside hand-crafted golden stucco and an elaborate wooden ceiling. Low brown sofas surround massive platters of inscribed copper, respecting Eastern traditions. The walls recite an ode to Moroccan traditions that the plates echo.

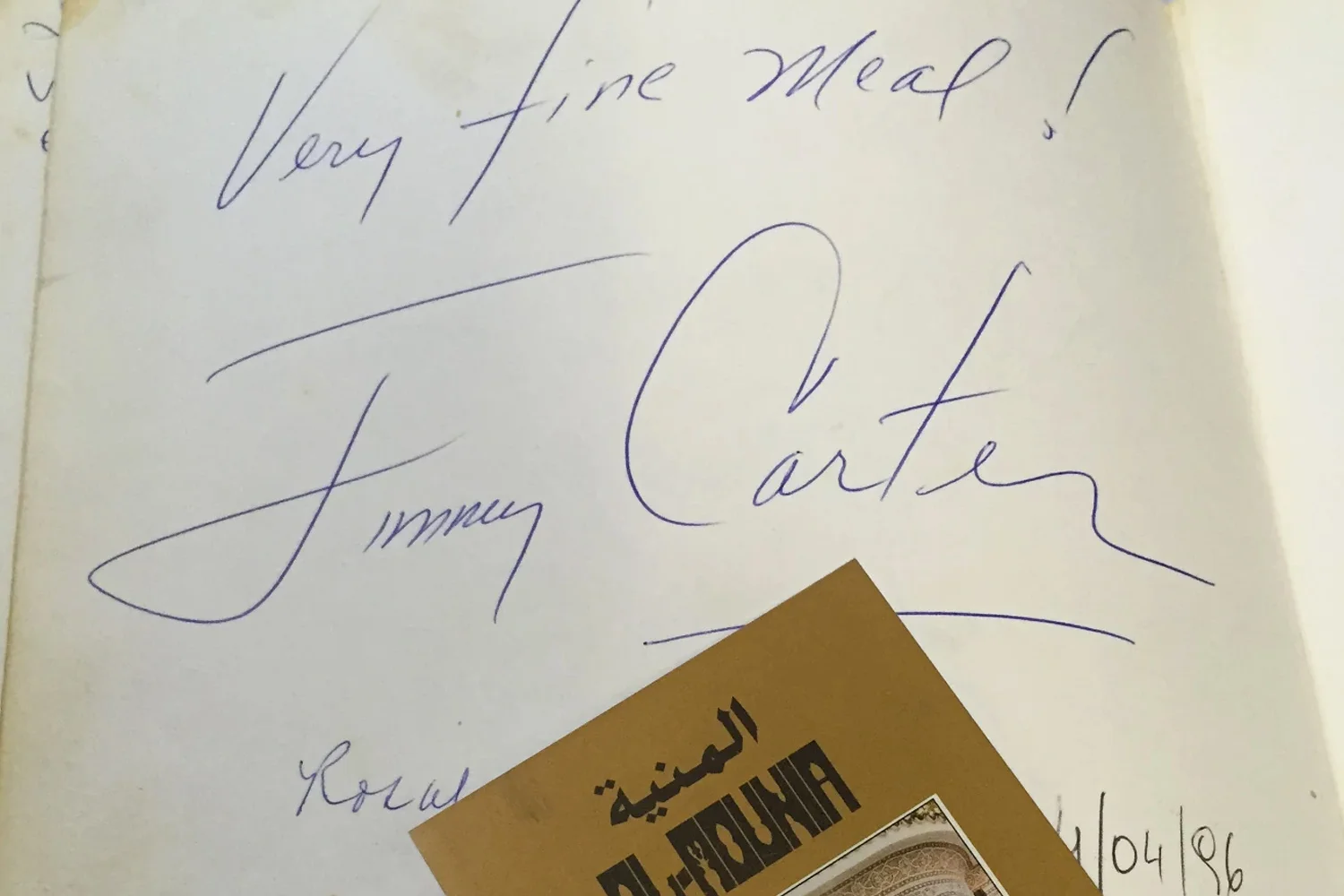

In the kitchen, a woman and a man form a complementary cooking couple, loyal to the establishment for more than 30 years. The menu has not changed and the ritual of eating remains the same: bastilla and briouates as a starter to a heartwarming couscous and flavoured meat tajine. At a time when contemporary chefs reinvent the codes and molecular gastronomy hits the headlines, Al Mounia looks into the past. There, local government officers, seeking the reassurance of their mother’s comfort food, mix with informed travelers and foreign state officials and celebrities, curious to unveil Moroccan traditions.